Last week, we marked the welcome news that Karen Tei Yamashita’s I Hotel was named as one of the five finalists for the National Book Award for Fiction. As we mentioned, Amerasia has had a long-running relationship with Yamashita, going as far back as 1976, when we published her short story “The Bath.” Below, we are reprinting an excerpt from “The Bath,” along with portions of two interviews with the author and a critical piece about her writing. In particular, the interviews provide valuable background and context to Yamashita’s work.

For those interested in reading more by and about Karen Tei Yamashita in Amerasia, we have provided links to the pieces, available via Metapress. (Registration with Metapress is required for the PDF downloads of the articles.)

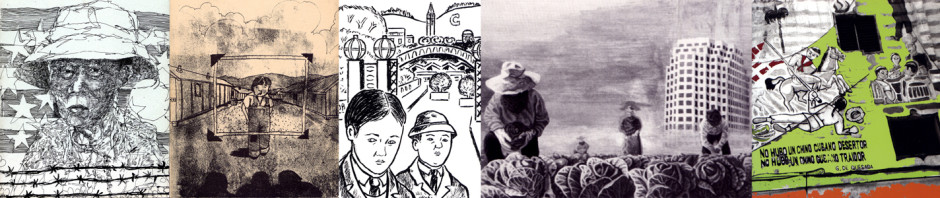

Karen Tei Yamashita atop the new International Hotel, 30th anniversary of the eviction of International Hotel tenants. © Mary Uyematsu Kao, 2007

“The Bath” (1976)

By Karen Yamashita

(Note: “The Bath“ is the first-place winner in Amerasia Journal’s Short Story Contest for 1975.)

In their house they have often said that mother has a special fascination for the bath. Father pointed this out many years ago. Perhaps it was only in answer to mother’s suggestion that father might take a bath more frequently. Remembering, father seemed to take baths once a week on Saturday nights. Father bragged of his once a week bath but only in relation to mother’s nightly affair. Over the years, it seems mother has taken to early morning baths as well, so father’s comments on mother and the bath continue with an added flourish.

He seems to believe that certain of mother’s habits have come together to conspire against him by beginning all at once in the morning….

The complete story is available at Amerasia Journal 3:1 (1976): 137-152.

More on Karen Tei Yamashita from the pages for Amerasia after the jump…

Karen Tei Yamashita: An Interview with Michael S. Murashige (1994)

Michael S. Murashige was working on his Ph.D. in English at UCLA at the time that the interview was conducted.

Though Karen Tei Yamashita lives in Gardena, California, with her husband Ronaldo, and her two children, Jane and Jon, she spent nine years in Brazil beginning in 1975. Yamashita travelled there on a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship to study Japanese immigration to Brazil. But what started out as a one-year project turned into a nine-year stay during which she got married, raised a family, and began her career as a writer with the two books that grew, more or less, out of her experiences during that nine-year period, Through the Arc of the Rain Forest and Brazil-Maru. After her return to Southern California in 1984, she continued to work creatively, writing pieces on Brazil for a local Japanese American newspaper, the Rafi Shimpo, translations of Brazilian literature and, most notably, a number of multimedia / stage performances including Hannah Kusoh: An American Butoh, Tokyo Carmen us. L.A. Carmen, and a musical, GiZAwrecks in collaboration with composer Vicki Abe.

What follows is only a small portion of a larger interview in which I had the chance to listen to Yamashita talk at length about the beginnings and development of her two novels, her thoughts on Brazil, social critique, and her work in the theater. Though the scope of Yamashita’s interests is truly international-from the United States to Japan to Brazil and back-I noticed (or maybe Iimagined) an unmistakable Gardena Japanese Americanness that I hope finds its way into her next novel which takes place in Los Angeles.

MM: In your first book, Through the Arc of the Rainforest, you give what seems to be a panoramic view of Brazil. Besides telling a story that involves so many different characters and places, was there anything about Brazil, specifically, that you were trying to capture?

KTY: That book was written here in this country after being in Brazil for nine years. I guess it was a way for me to pull together that experience of being in Brazil for nine years in my own fashion. And it’s funny, every now and then I‘ll meet people who lived in Brazil for any number of years who also read my book and they say, ”You know, there’s something you can’t describe that is here. And this is how it feels to be in Brazil.” And I think that’s funny, but I think that is. That’s why, in my mind, the whole idea of it being any sort of magic realism is really on the edge of making no sense. Especially when you live in a country like Brazil that has a very middle-class structure which involves international technology-a technology that comes from this country and from Japan-and at the same time, next door, you have people who have no relationship to that technology or use that technology in a manner that has nothing to do with it.

As Ronaldo [Yamashita’s husband] says, ”You may go to a small, rural place and the person there has gone to a lot of trouble to buy a refrigerator but he has no electricity to hook the damn thing up. So what does he use the refrigerator for? Well, when you open the refrigerator you’ll find that it’s storage.”

Continue reading the interview at Amerasia Journal 20:3 (1994): 49-59

Interview with Karen Tei Yamashita with Te-hsing Shan (2006)

Te-hsing Shan is a Research Fellow at the Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica, Taiwan and Chair Professor at the Department of English Language, Literature and Linguistics, Providence University.

TS: You were born in California in 1951 as a third-generation Japanese American. Can you say something about your family’s immigration history? How does it affect your way of looking at the world and your writing?

KTY: I was born in Oakland in the Bay Area. My mother’s father came to San Francisco before the turn of the century. Soon after the earthquake of 1906, he and my grandmother opened a grocery store, the Uoki Sakai Fish Market on Post Street, currently right opposite the Miyako Hotel in Japantown, San Francisco. Now my cousins run the store, and the store will be 100 years old this year.

My father’s father was from a small village near Nakatsugawa in Gifu. He came to the United States also around the turn of the century to study tailoring. He went back to marry my grandmother in Tokyo. They returned to start a family in Oakland and opened a tailor shop called Yokohama Tailor.

My father was born in Oakland, and my mother was born in San Francisco and grew up in Japantown. That’s the story I know.

Did it affect my writing? Yes, but you don’t know these things at the time. When I was in college, I went to Japan for the first time. That was in the 1970s. I studied in Tokyo. Before I left, I heard Alex Haley speak. He came to Carleton College, where I was studying. We went to hear him because he had written the Autobiography of Malcolm X, but after talking about Malcolm X, he talked about his own family story. I heard that story many years before he ever published the book….

Continue reading at Amerasia Journal 32:3 (2006): 123-142.

Forging a North-South Perspective: Nikkei Migration in Karen Tei Yamashita’s Novels

By Jinqi Ling

Jinqi Ling is Associate Professor of English and Asian American Studies at UCLA. He is the author of Narrating Nationalisms: Ideology and Form in Asian American Literature (Oxford, 1998). He is currently working on a book project that deals with transnationality, class, interracial relations, and surrealism in Asian American literature.

“. . .the North of my dreams. . .South of his dreams. . .”

—Tropic of Orange, Karen Tei Yamashita

Karen Tei Yamashita’s works of fiction on Nikkei migration, mostly written during the last decade of the twentieth century and using Latin America as their central frame of reference, recognize and reinscribe the contemporary and historical linkages of Asian Americans to South America. Her provocative redefinition of the spatial, metaphorical, and linguistic boundaries of Asian American literature has been both enabling and frustrating to her readers across traditional and emerging disciplinary concerns. This article assesses the significance of Yamashita’s attempts through an examination of three of her novels that focus on Japanese-Brazilian interaction: Through the Arc of the Rain Forest (1990), Brazil-Maru (1992), and Circle K Cycles (2001). Previously, Asian American literary studies have been largely informed by U.S.-centered historical research and by premises originating in Edward Said’s critique of Orientalism. Recent investigations of Asian American literary production, however, self-consciously foreground a transnational perspective, emphasizing the multiple trajectories of Asian diasporas, the transcendental force of commercial market, the fluidity of cyberspace, and the growing impact of Asian capitalisms. Yet many such efforts do not go beyond normative postnational procedures and the larger map of a now reified East- West analysis. Consequently, they often end up affirming the rhetorical underpinnings of a U.S.-inspired imaginary of mobility, while they continue to ignore the ongoing social predicaments of the global South, which in many cases remains on various Western neocolonialisms.

Continue reading this essay at Amerasia Journal 32:3 (2006): 1-22

Amerasia on Facebook!

Amerasia on Facebook!