Aoki Film Screening set for March 12, 2011 4-7 p.m.

Given the minor calamity of the time change, the AOKI screening mobilization is on. Due to the funeral of a prominent Japanese American community member, we had to readjust our time slot at Centenary Methodist Church for the film screening. But now its no holds barred, and spreading the word is ON. We have the additional draws that you should know about besides the screening of “AOKI: A DOCUMENTARY FILM.” The Richard Aoki Tribute Committee is excited and very grateful to have Diane Fujino and Sherwin Forte for the Q&A after the film.

Given the minor calamity of the time change, the AOKI screening mobilization is on. Due to the funeral of a prominent Japanese American community member, we had to readjust our time slot at Centenary Methodist Church for the film screening. But now its no holds barred, and spreading the word is ON. We have the additional draws that you should know about besides the screening of “AOKI: A DOCUMENTARY FILM.” The Richard Aoki Tribute Committee is excited and very grateful to have Diane Fujino and Sherwin Forte for the Q&A after the film.

Sherwin Forte was one of the original first six members of the Oakland Black Panther Party. The original six were: Bobby Seale, Huey P. Newton, “Little” Bobby Hutton, “Big Man” Elbert Howard, and two brothers, Reggie and Sherwin Forte. He is still a community activist.

Diane Fujino is author of the forthcoming book Samurai Among Panthers: The Life and Times of Richard Aoki (University of Minnesota Press in Spring 2012). She is a scholar-activist and chair of the Department of Asian American Studies at the University of Caifornia, Santa Barbara.

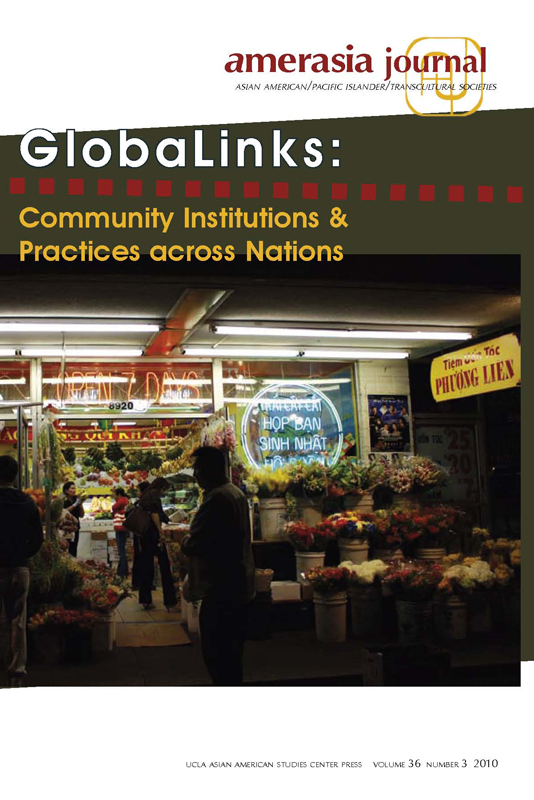

Amerasia 36:3 – GlobaLinks: Community Institutions & Practices across Nations

Amerasia 36.3

GlobaLinks: Community Institutions & Practices across Nations

Los Angeles — The UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press announces the publication of Amerasia Journal’s latest issue, “GlobaLinks: Community Institutions & Practices across Nations.” Guest edited by Michel Laguerre and Joe Chung Fong, both of the Berkeley Center for Globalization and Information Technology, the special issue brings together research on globalized diasporic communities in the U.S. and Asia from scholars based throughout the Pacific Rim. The contributions to “GlobaLinks” provide new insights on Asian American spaces and places from a wide array of intellectual perspectives, including history, cultural anthropology, urban studies, sociology, ethnic studies, and political science.

“GlobaLinks” recognizes that Asian and Pacific American communities are no longer limited by their institutional identities within local boundaries or defined by their political, cultural, or economic activities within national borders alone. Amerasia has worked with our guest editors to put together a selection of studies which examine social phenomena such as the self-political identity of communities, trans-Pacific youth, banking, voting and political campaigns, and community cultural development. At a conceptual and theoretical level, “GlobaLinks” urges scholars to rethink and reconsider what key terms such as “globalization” and “transnationalism” mean in light of rapidly changing Asian and Pacific American communities. In his introductory essay, for instance, Michel Laguerre coins the term “cosmonation” to make the case that the global and the local are mutually implicated in a complex network of relationships that is not “top-down” or hierarchical as a nation-oriented model of homeland and hostland is.

More information on “GlobaLinks” below the fold…

Call for Abstracts: The State of Illness and Disability in Asian America

Amerasia Journal Special Issue Call for Papers

The State of Illness and Disability in Asian America

Guest Editors: Professor Jennifer Ho (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) and Professor James Kyung-Jin Lee (University of California, Irvine)

We seek critical essays and articles as well as creative non-fiction and first-person accounts that engage with the intersections of Asian American discourse and illness/disability studies, for a special issue of Amerasia Journal, scheduled for publication in 2012.

Since, as scholar Michael Berube observes, “the definition of disability, like the definition of illness, is inevitably a matter of social debate and social construction,” we are interested in how these social constructions of disability and illness coincide, collide, and converge with those of ethnicity and race, along with other axes of intersectionality such as gender, sexuality, class, region, religion, age, and education. Critiquing the narrow perspective of the discipline, scholar Chris Bell has noted “the failure of Disability Studies to engage issues of race and ethnicity in a substantive capacity, thereby entrenching whiteness as its constitutive underpinning.” One goal of this special issue is to provide another forum in which to challenge entrenched whiteness within Disability and Illness Studies as well as to bring to the foreground the state of illness and disability within the Asian American community.

Contributors to this special issue may consider the following questions:

• What is the role of illness and disability within Asian American narratives—be they in fiction, non-fiction, or cinematic form—and/or how is the ill or disabled Asian American body represented within these narratives?

• How are illness and disability regarded within Asian American communities and cultural productions?

• What are the special needs of Asian Americans who face life threatening and chronic illnesses?

• What kinds of accommodations do Asian Americans with disabilities find most challenging in light of their ethnic and cultural backgrounds and/or as a result of their racialization as non-white Americans?

• How might Asian American experiences of disability and/or illness invite a reimagination of what constitutes a “good” life practice or way of living, and what kinds of social transformations would be necessary to make this so?

Submission Guidelines and Deadlines:

Due Date for one-page abstracts: June 15, 2011

Due Date for solicited final papers: January 2012

Publication Date: Fall 2012

The editorial procedure involves a three-step process: The guest editors, in consultation with the Amerasia Journal editors and peer reviewers, make decisions on the final essays:

- Approval of abstracts

- Submission of papers solicited from accepted abstracts

- Revision of accepted peer-reviewed papers and final submission

Please send correspondence regarding the special issue on illness and disabilities studies in Asian American Studies to the following addresses. All correspondence should refer to “Amerasia Journal Disabilities Studies Issue” in the subject line.

Professor Jennifer Ho: jho@email.unc.edu

Professor James Kyung-Jin Lee: jkl@uci.edu

Arnold Pan, Amerasia Journal: arnoldpan@ucla.edu

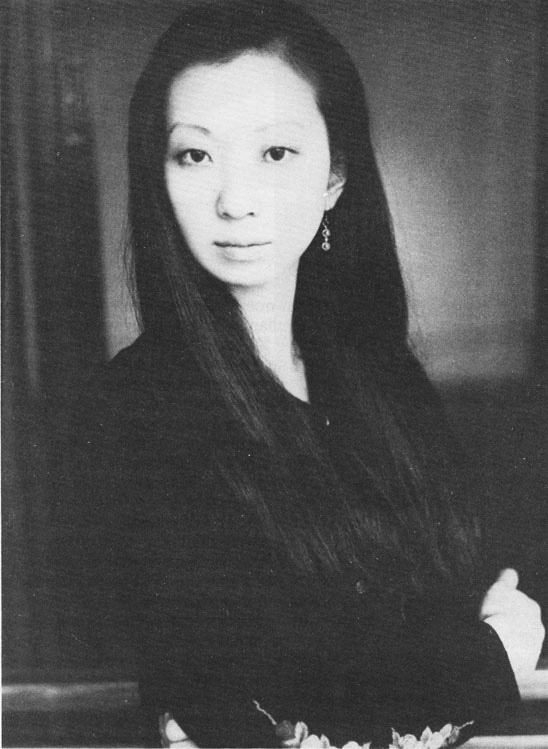

Fae Myenne Ng Reading of her second novel Steer Toward Rock

Fae Myenne Ng (author of Bone) will read and discuss her second novel

Steer Toward Rock

March 29, 2011 Tuesday at 5:00 p.m. at Eastwind Books of Berkeley

2066 University Ave. Berkeley, CA 94704

For more information (510)548-2350

email: eastwindbooks@gmail.com

“The woman I loved wasn’t in love with me; the woman I married wasn’t a wife to me. Ilin Cheung was my wife on paper. In deed, she belonged to Yi-Tung Szeto. In debt, I also belonged to him. He was my father, paper too.”

Steer Toward Rock, Fae Myenne Ng’s heartbreaking novel of unrequited love, tells the story of JMS, the only bachelor butcher at the Universal Market in San Francisco. He is a man forced to choose between love and the law.

Not since Bone, Fae Myenne Ng’s highly praised debut novel, has a work so eloquently revealed the complex loyalties of Chinese America. Inspired by the Old Bachelors community in San Francisco Chinatown and the effects of the Chinese Exclusionary Act of 1882, Steer Toward Rock explores how the Chinese Confession Program targeted the community for racial persecution, interrogation, and deportation.

With the insight of a writer who knows the streets and alleys of Chinatown, Ng brings her readers into the lives of this community.

“This is an always gorgeous and often terrifying love story. It’s a poetic study of loyalty, love, loneliness, hard work, identity, immigration and political paranoia. I sing an honor song for Fae Myenne Ng’s return with her new novel.”

—Sherman Alexie, author of The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian

“Fae Myenne Ng writes like a bebop jazzer, a Miles Davis trumpet solo, tough and trenchant, moody and poetic, erratic and explosive, with surprising lines leading to beauty and truth. “ —Ben Fong-Torres, author of Rice Room, former editor of Rolling Stone.

Serving the public since 1982 and onwards.

Become a fan of Eastwind Books of Berkeley on Facebook! http://www.facebook.com/eastwind.books

More thoughts on the passing of Hisaye Yamamoto

Long-time Amerasia Journal Editor Russell Leong and Professor King-Kok Cheung, who wrote the introduction to the collection Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories, share their thoughts on the passing of Hisaye Yamamoto:

Long-time Amerasia Journal Editor Russell Leong and Professor King-Kok Cheung, who wrote the introduction to the collection Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories, share their thoughts on the passing of Hisaye Yamamoto:

It is Hisaye who has been the model for many of us–exploring new territories of gender, race, sexuality, etc.–even before the term “Asian American literature” ever existed. “A Fire in Fontana,” “Seventeen Syllables” and “High-heeled Shoes” are classics of American literature. She, and others such as N.V.M. Gonzalez and Carlos Bulosan, early on delved into the complexities of literary form amidst social chaos and made urgent sense of what they saw. They swept aside the residue of colonialism, racism, and sexism and cast a burning light to illuminate literature. Their works glow in the firmament of our imagination and belong forever to the universe. I see their words racing across constellations, creating new meanings for us who find ourselves yet among the living. Let us continue to read.

Russell Leong, New York City, NY

No contemporary writer has touched my heart, mind, and spirit as much as Hisaye Yamamoto. Whether writing about aborted creativity (“Seventeen Syllables”), doomed romance (“Epithalamium”), the dubious norms for sanity and insanity (“The Legend of Miss Sasagawara” and “Eucalyptus”), the havoc wrought by addictive gambling (“The Brown House” and “Las Vegas Charley”), or the debilitating effect of racism (“Wilshire Bus” and “A Fire in Fontana”), she does so with abiding compassion, keen eyes, wry humor, and prose that is at once disarming and harrowing.

Professor King-Kok Cheung, UCLA

Aoki: Two Years in Passing and Still Being Remembered

Still on the trail of the Black Panther Party, one of the lesser known Black Panthers was a Japanese American by the name of Richard Aoki. Amerasia Journal ran a “Passages” section in the issue entitled “Subjugated to Subject: Through Class, Race and Sex” (Volume 35, Number 2, 2009) that honored him. This section chronicled the passing of four huge luminaries of the Asian American Movement: Him Mark Lai, Ron Takaki, Al Robles, and Richard Aoki.

Still on the trail of the Black Panther Party, one of the lesser known Black Panthers was a Japanese American by the name of Richard Aoki. Amerasia Journal ran a “Passages” section in the issue entitled “Subjugated to Subject: Through Class, Race and Sex” (Volume 35, Number 2, 2009) that honored him. This section chronicled the passing of four huge luminaries of the Asian American Movement: Him Mark Lai, Ron Takaki, Al Robles, and Richard Aoki.

A Los Angeles Richard Aoki Tribute Committee is hosting a free film showing of “Aoki: A Documentary Film” by Ben Wang and Mike Cheng on March 12, 2011 to commemorate the second anniversary of Richard Aoki’s death. (For more information, see the flyer to the right.)

Excerpts from “Richard Aoki (1938-2008): Toughest Oriental to Come Out of West Oakland,” by Harvey Dong (published in the “Passages” section), provide some history of an Asian American greats who has passed on:

. . .a quote by Richard:

. . .Based on my experience, I’ve seen where unity amongst the races has yielded positive results. I don’t see any other way for people to gain freedom, justice, and equality here except by being internationalist.

More excerpts, after the jump…

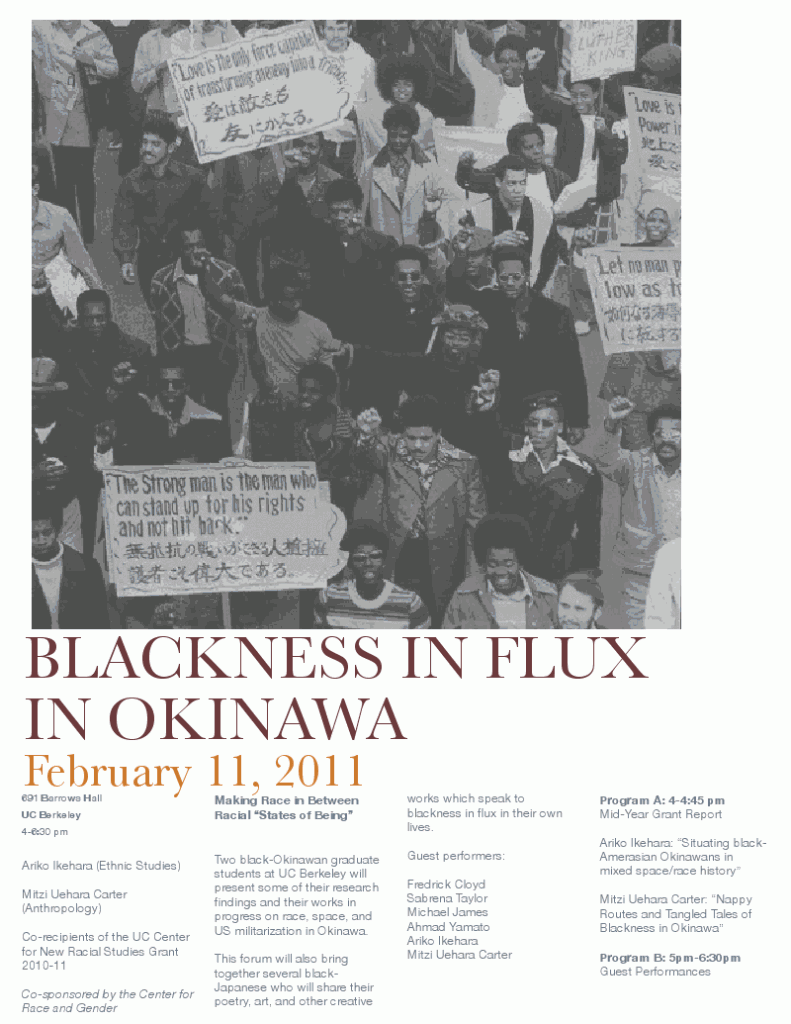

Blackness in Flux in Okinawa, Feb. 11, 2011 @ UC Berkeley

Sabrena Taylor, past Amerasia contributor to “No Passing Zone: The Artistic and Discursive Voices of Asian-descent Multiracials” (Volume 23, No. 1 1997) will be doing a poetry reading at this event.

Sabrena Taylor, past Amerasia contributor to “No Passing Zone: The Artistic and Discursive Voices of Asian-descent Multiracials” (Volume 23, No. 1 1997) will be doing a poetry reading at this event.

Introductions to “Where Women Tell Stories”

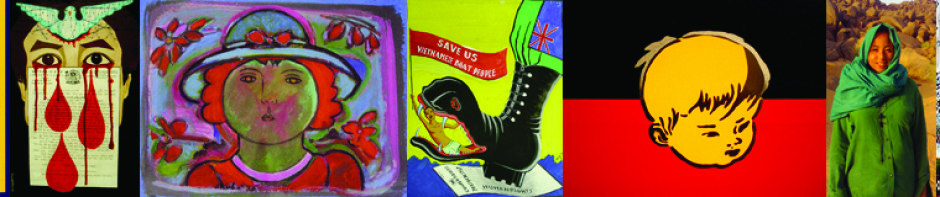

Following are two introductions to Amerasia‘s women’s issue “Where Women Tell Stories” by guest editors Stephanie Santos and Mary Uyematsu Kao. Accompanying the text are more photos from the “Buildin’ Bridges and Stirrin’ Waters” event on November 5, 2009 at UCLA’s Powell Library Rotunda.

Introduction

Ethical Dialogues

When we began working on this journal, I thought this issue of Amerasia was going to be a feminist issue. However, feminism—mainstream liberal feminism to be exact—was inadequate in articulating the narratives and knowledge of Asian American women. Jacqui Alexander wrote that to address liberal feminism’s ingrained sexual and racial mythologies, feminists must “become fluent in each other’s histories.” In this issue, we attempt to contribute to this greater fluency, initiating dialogue by bringing in the herstories of Asian American women.

Chandra Mohanty wrote of the challenges that lie in crafting noncolonized dialogues to enable a critical, multicultural feminism. Such dialogues are necessarily fraught with tension, because they entail destabilization and decentering of the traditional referents of white, mainstream, liberal feminism. One way to begin, suggests Mohanty, is to figure out how to “engage in ethical and caring dialogues across the divisions, conflicts, and individualist identity formations that interweave feminist communities in the United States.”

The articles in this issue attempt to build ethical and caring dialogues between these divisions. What happens when feminism, for example, is centered around the needs and concerns of immigrant garment workers in New York’s Chinatown? Katie Quan, in “Memories of the 1982 ILGWU Strike in New York Chinatown,” remembers the strike staged by members of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), and the significance of organizing in the lives of the union members, as well as to the larger community. She writes, “The women participated in union activities, but also in non-labor events. . . . Labor and community were seamlessly integrated—what was good for workers was good for the community, and vice-versa.

What happens when feminism is centered around the needs and concerns of immigrant mothers of color? Laura Pulido, in “Immigration Politics and Motherhood,” notes how despite efforts to unite women based on “a general politics of motherhood,” mainstream feminists have not offered any real support to mothers from politically subordinated groups, such as immigrant women. Pulido’s article highlights how the motherhood of “racially and socially despised” mothers remains unrecognized by mainstream feminists. In fact, Pulido argues that motherhood’s potential to link diverse constituents is often thwarted by nativism and racism.

What happens when feminism is centered around the needs and concerns of transnational Filipinas and Filipina Americans, who collaborate within an “ever changing terrain of women’s organizing?” Annalisa V. Enrile and Jollene Levid, in their article “GABNet: A Case Study of Transnational Sisterhood and Organizing,” acknowledge the challenges of transnational organizing. Their response to Mohanty’s call for crafting ethical dialogues includes “a transformative style [of] organizing that is guided by actions and political campaigns in the Philippines but made concrete in the United States, sensitive to context and situation of the American mainstream and the marginalized Filipino immigrant communities.”

Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales and Jocyl Sacramento, in their article “Practicing Pinayist Pedagogy” contribute further to decentering mainstream liberal feminism. For the authors, Pinayism is a praxis that allows Pinays to “connect the global and local to the personal issues and stories of Pinay struggle, survival, service, sisterhood, and strength.” Through discussions of concrete pedagogical strategies such as boodoo doll creation and critical performance, Tintiangco-Cubales and Sacramento go beyond mainstream feminism to “engage the complexities and intersections” of multiple Pinay subjectivities, which in addition to gender also encompass, among other factors, class, race/ethnicity, spirituality, educational status, diasporic migration, and citizenship.

This issue of Amerasia Journal begins with articles grouped under the section “Narrative,” as many of the articles deal with giving voice to herstories that have been subjugated. Jolie Chea, in “Refugee Acts,” engages in an act of critical remembering as a way to subvert hegemonic historical accounts, writing “(t)hrough my grandmother, I have learned to see and listen to mouths that were not speaking, but bodies that were being. . .to think of new, alternative ways of seeing, to contest that which has already been established and not by our own selves, but by others.” In “Mother, May I?,” Carrie Usui shares how a shared type II diabetes diagnosis allowed her mom and herself to move “in between mother and daughter lines, between caregiver and person in care, learning together in how to live this new life, while at the same time better understanding our pasts.”

The second section, “Power,” addresses the themes of collaborations between women of color, between activists for social justice.

We end with a section on “Knowledge,” often painfully gained from the place-making and activist efforts detailed in the first two sections. “This work [organizing around women’s issues] can also be dangerous,” writes Ketu Katrak in her article “Transnational Links: South Asian American Women’s Organizations and Autonomous Women’s Groups in India,” since activists risk greater violence. “It may be as strategic,” Katrak states, “to subvert the system from within. . .and to live another day in order to tell one’s story.”

Though this is the first Amerasia Journal specifically designated a “women’s issue,” it is not the first time that Amerasia has dealt with issues affecting women. However, we do recognize that both feminist analysis and ethnic studies have weaknesses in articulating the herstories of Asian American women. This issue is our own attempt to craft bridges between these discussions. It is our hope that other scholars and activists would in turn fill in the gaps and elisions in the work that was begun here.

Initially, I approached this issue of Amerasia Journal as a feminist issue, one that would highlight the key tenets of Asian American feminisms. I have since seen how sexist oppression by itself is not an inclusive enough foundation on which to build feminist solidarity. In fact, this formulation leads to what Roshni Rustomji identifies as a “salvation” narrative in her article “Subverting the Hierarchy, Collaborating Narratives.” Feminists who are privileged through factors like race, class, or citizenship get trapped into the mindset of asking, “What can I do for them?” This is a feminism still centered on oneself as a referent, one who is acting for and not in solidarity with the Other.

bell hooks offers a powerful method of shifting this emphasis by recasting the phrase “I am a feminist” into “I advocate feminism.” hooks has defined feminism as “a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression.” hooks’ recasting allows us to focus on ending sex- and gender-based oppressions by addressing their many intersecting causes. Emphasizing the action of advocating feminism, instead of a feminist identity, also allows for more dynamic political involvements, whether with undocumented mothers, refugees, immigrant garment workers, or social justice activists.

This is perhaps my roundabout way of saying that despite my misgivings about the term, I see this Amerasia Journal women’s issue as an issue that advocates feminism—one that contributes to the practice of multicultural and antiracist feminisms.

—Stephanie D. Santos

Virtual Sisterhood

Somehow, since the 1960s and 70s, sisterhood got sideswiped by “feminism.” For some of the younger generations, they are being sold a bill-of-goods that feminism is all about “self-empowerment.” Self-empowerment is good for every healthy human being, especially in the kind of society we are living in here in the U.S. But self-empowerment has been commodified, just as having an African American president has become America’s latest commodification in an attempt to drag our asses out of a huge financial abyss. Self-empowerment has been repackaged away from its original intents, and now comes at us as straight-up individualism to enable you to play the capitalist rat-race game of dog-eat-dog social norms. This weakens a people and keeps you divided so you can remain conquered. The dynamics of today’s situation with social and political movements of the left in total disarray, this really has to be a soul-searching time on the real lessons learned from the 1970s movements.

More from “Virtual Sisterhood,” below the fold…

Amerasia on Facebook!

Amerasia on Facebook!